The real secret to building problem-solving skills isn't about giving children the answers. It’s about shifting our role from instructor to guide. It means modelling what it looks like to be curious, feeling the frustration of a challenge, and, most importantly, celebrating the courage to try—not just the final solution. This subtle shift helps nurture a growth mindset, giving your child the emotional tools they need to face life’s challenges with a brave and open heart.

Why Problem Solving Is a Core Life Skill for Your Child

As parents, what we want most is for our children to thrive in a world that’s constantly changing. Of course, academic results matter, but the true foundation for a happy and successful life is built on something deeper: the ability to face a challenge, feel the uncertainty, and find a way forward.

This is the heart of problem-solving.

It’s so much more than just finishing a tricky maths problem or a jigsaw puzzle. It’s the flicker of pride a child feels when they finally tie their own shoelaces after days of fumbling. It's the quiet confidence they build after navigating a disagreement with a friend in the playground. These are the moments that count—the ones that whisper, "You can do hard things."

The Four Pillars of Problem Solving

To really understand what your child is going through when they face a problem, it helps to break it down. I find it useful to think of it in terms of four key pillars. Understanding these can help you spot opportunities to nurture these skills in everyday life.

| Pillar | What It Means for Your Child | A Quick Example |

|---|---|---|

| Understanding the Problem | Can they explain the challenge in their own words? This shows they’ve really grasped what they’re up against. | Their LEGO tower keeps falling. Instead of getting frustrated, they can say, "The bottom part isn't wide enough and it makes it wobbly." |

| Making a Plan | Thinking about the steps needed before jumping in. It’s about strategy, not just action. | "Okay, first I'll build a bigger base with the big flat pieces, then I'll add the smaller bricks on top." |

| Trying It Out | This is the action phase, where they put their plan to the test and see what happens. It's where they feel the hope and anticipation. | They start building again, carefully following their new plan to create a sturdier foundation for their tower. |

| Looking Back | Reflecting on what worked and what didn't. This is where the deepest learning happens and they feel that sense of accomplishment. | The tower is now stable. They realise, "A wide base is really important for tall towers! I did it!" |

These pillars aren’t just a one-off checklist; they form a cycle. Every time your child works through this process, they’re strengthening their ability to tackle the next, bigger challenge.

Moving Beyond Academic Scores

Problem-solving is the engine of independence. It’s a skill that serves your child for life, not just for the next exam. When we focus on teaching them how to think instead of just what to think, we give them a gift that will last a lifetime. This skill is also deeply connected to other vital abilities, like the ones we explore in our guide on how to develop critical thinking skills.

Recent UK government data really brings home why starting early is so important. The findings revealed that just 72% of children between 2 and 2.5 years old were meeting the expected levels for problem-solving. This isn't a reason to panic, but it does highlight how much our little ones need us to be intentional about building these skills at home.

When we shift our role from being the 'provider of answers' to the 'guide on the side,' we empower our children. We're not just helping them solve the problem at hand; we're teaching them they are capable of solving the next one, and the one after that, all on their own.

The Emotional Side of Solving Problems

The journey of becoming a problem-solver is an emotional one. Every small victory, from building that wobbly tower of blocks to finally beating a tricky video game level, is a deposit into a child's bank of self-esteem. It teaches them that frustration is a normal part of the process—a sign that you're learning something new—and that persistence really does pay off.

This is especially powerful for children with Special Educational Needs (SEN) or those facing Social, Emotional, and Mental Health (SEMH) challenges. For them, breaking a big task into tiny, manageable steps can turn an overwhelming wave of anxiety into a series of achievable wins, building a crucial sense of control and self-worth.

By framing everyday hurdles as learning opportunities, you build a powerful partnership with your child. You show them that it's okay not to have the answer straight away and that the real magic is in the journey of figuring it out together. For a more detailed look at specific techniques, it's worth exploring how to improve problem-solving skills. This journey truly prepares them for a future where they can face anything that comes their way with a calm, clear mind.

Creating a Safe Space for Problem Solving at Home

The journey to becoming a confident problem solver rarely starts with complex puzzles or formal lessons. It begins at home, with the quiet feeling that it’s safe to try, to get stuck, and even to fail without losing your love and support.

As parents, our instinct is often to rush in and fix things, to soothe their distress by taking over. We can't bear to see them struggle, whether it's with a tangled shoelace or a frustrating bit of homework. But to truly help our children develop problem-solving skills, we need to make a gentle but profound shift in our role—from the family’s designated ‘fixer’ to a patient ‘thinking partner’.

This all starts with creating an environment where curiosity is celebrated and mistakes are just seen as part of the learning process. It’s about building a space where your child feels emotionally secure enough to say, “I’m stuck,” without fearing disappointment or judgement. When they know you value their effort far more than the correct answer, their entire mindset begins to change. They learn that the real victory isn't getting it right the first time, but having the courage to try again.

From Fixer to Thinking Partner

Making this shift can feel unnatural at first, especially when you’re short on time. It’s always quicker to tie the shoes yourself. But resisting that urge to take over is one of the most powerful things you can do for your child’s development.

Instead of jumping in with the solution, try using empathetic phrases that validate their feelings while encouraging them to keep going:

- "That looks really tricky. I can see you're getting frustrated, and that's okay." This acknowledges their emotion without taking the problem away.

- "What's the first thing you tried? What do you think you could try next?" These open questions gently guide their thinking process.

- "I remember finding this so hard when I was your age. It's a tough one! Let's take a deep breath together." This normalises the struggle and models a healthy coping strategy.

Imagine your child is building a tower that keeps collapsing, and tears are welling up. Instead of showing them how to build it properly, you could sit with them, put an arm around them, and say, "Oh, that's so frustrating when that happens. It feels awful. What do you notice about the blocks at the bottom when it starts to wobble?" This small change in language shifts the focus from your solution to their observation, putting them firmly in the driver's seat of their own learning.

The goal isn't to prevent your child from ever feeling frustrated. It's to teach them that frustration is a signal to think differently, not a reason to give up. By becoming their thinking partner, you're not just helping them with one problem; you're equipping them to face countless future challenges with resilience.

Thinking Out Loud and Modelling the Process

Children are fantastic mimics. They learn far more from watching how we handle our own struggles than from hearing what we say. One of the most effective ways to teach problem-solving is simply to model your own thinking process out loud. Let them hear the internal monologue we all have when faced with a challenge.

This demystifies the idea that adults just magically know the answers. It shows them that problem-solving is a messy, step-by-step process for everyone.

Practical Examples of Thinking Out Loud:

- In the Kitchen: "Oh no, the recipe says we need buttermilk, but we don't have any. I feel a bit stuck! Hmm, I wonder what we could use instead? I remember reading that a little bit of lemon juice in regular milk works. Let’s try that and see what happens."

- Planning an Outing: "Okay, we want to go to the park on Saturday, but the weather forecast says it might rain. I'll feel so disappointed if we can't go. What's our backup plan? Maybe we could go to the library in the morning and check the forecast again before we decide."

- Putting Together Furniture: "Right, these instructions are a bit confusing, and I'm starting to feel a bit overwhelmed. I'm going to lay out all the pieces first and match them to the pictures. That should make it easier to see what goes where."

By verbalising your own thought process—including your feelings of frustration or uncertainty—you demonstrate that it’s completely normal to feel this way. You're giving your child a blueprint for how to approach their own challenges. This simple practice builds their confidence and shows them that working through difficulties is a normal, manageable part of everyday life—a skill they can absolutely master.

Practical Strategies for Breaking Down Any Problem

Once you’ve created a safe emotional space for learning, you can start filling your child's toolkit with practical problem-solving methods. Thinking like a problem solver isn't an innate talent; it's a skill that can be taught. It often begins with one simple idea: making big, overwhelming challenges feel small and manageable.

The real magic happens when your child realises they already have the power to figure things out. Our job is to introduce them to simple, effective strategies they can lean on when they feel stuck, turning that flicker of frustration into focused, confident action.

Let's walk through three powerful, kid-friendly techniques you can start using today to help your child break down any problem they face.

The Power of Decomposition

Decomposition is just a fancy word for breaking a big, scary problem into smaller, bite-sized pieces. It’s a simple but brilliant technique that turns a feeling of "I can't possibly do this!" into a series of smaller, more encouraging "Okay, I can do that" moments. It works so well because it creates a clear path forward and builds momentum with every small win.

Think about a child faced with a messy bedroom. The single command, "Clean your room," can feel enormous, often leading to total paralysis and overwhelm. In reality, it isn't one task; it's dozens of tiny ones.

Using decomposition, we can reframe it together, sitting with them on the floor:

- "I know this feels like a huge job. Let's not even think about the whole room. First, let's just pick up all the LEGOs and put them in their box."

- "Great! Look at that clear space! Now, let's find all the books and put them back on the shelf."

- "We're doing so well. Next, we'll put all the dirty clothes in the laundry basket."

Each step is a small, achievable win that builds their sense of capability. This method isn't just for chores—it works wonders for homework, big school projects, and even learning a new skill. The goal is to show them how to find the very first step, and then the next, building their confidence along the way.

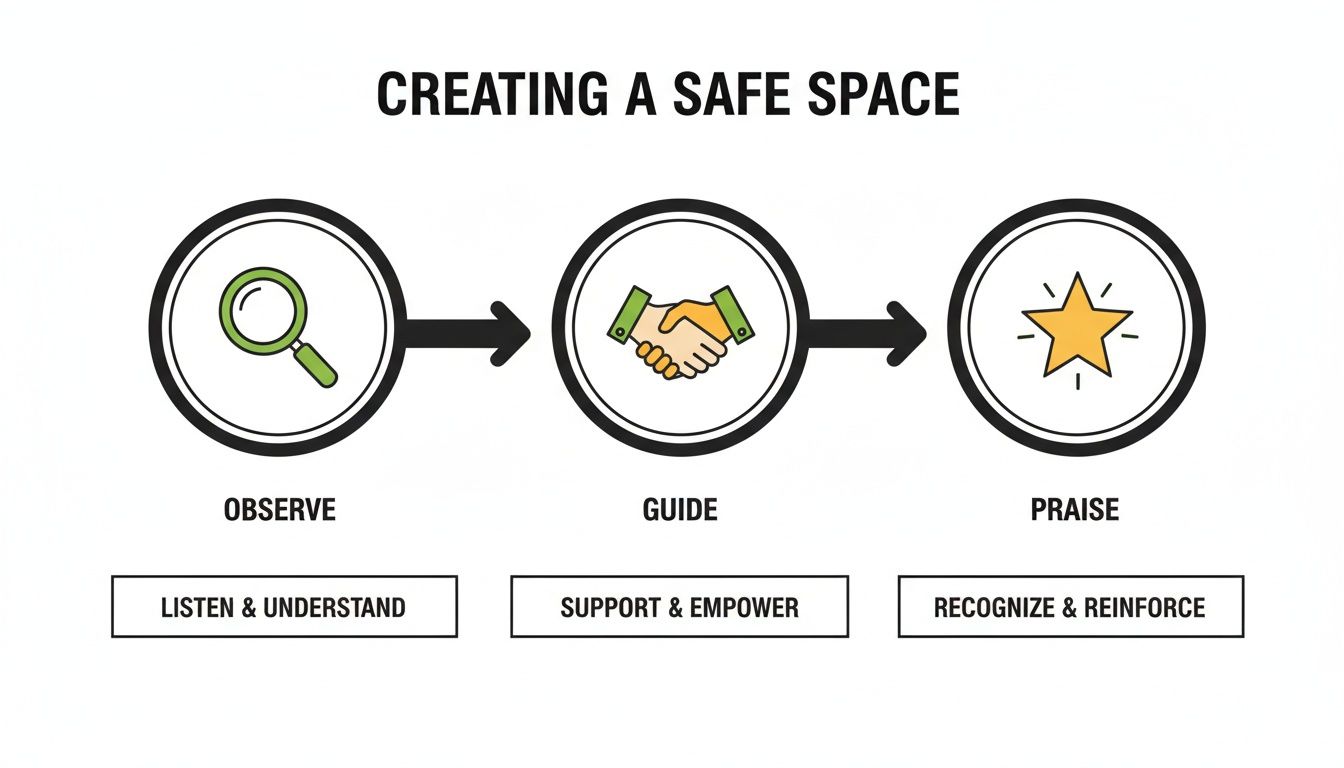

To help you guide this process, here is a simple flow for creating a supportive environment where these strategies can flourish.

This visual is a great reminder that our role is to observe first, guide gently, and always praise the effort. It creates the perfect conditions for your child to try new things without fear.

Finding Clues with Pattern Recognition

Our brains are natural pattern-detecting machines. Pattern recognition is all about teaching children to tap into this innate ability. It involves looking for similarities between the current problem and others they have already solved, helping them see that new challenges are often just variations of old ones.

Video games are a fantastic example of this in action. To beat a tough level, a child doesn't just randomly mash buttons. They start to spot patterns: "Ah, this enemy always jumps after it flashes three times." Once they see the pattern, they can predict what’s next and build a winning strategy.

You can encourage this skill in everyday life by connecting it to their world:

- Reading: "What do you notice about words that rhyme with 'cat'? They all have 'at' at the end! It's a pattern."

- Puzzles: "Look, all the edge pieces of this jigsaw have one flat side. That's a great clue. Let's find those first."

- Routines: "What's the pattern we follow every morning to get ready for school? It helps us feel ready for the day, doesn't it?"

By pointing out these connections, you're training their brain to actively hunt for clues and shortcuts. This makes them far more efficient and confident problem solvers.

Building Bridges with Analogical Thinking

Analogical thinking is a creative leap where a child uses a solution from one area to solve a problem in a completely different one. It’s about asking, "What does this feel like?" This technique encourages flexible, out-of-the-box thinking.

A brilliant, relatable analogy for a child is building with LEGOs. If they need to write a school report, the task can feel abstract and daunting, stirring up feelings of anxiety. But frame it like building a LEGO castle, and suddenly it clicks.

"I know writing a report feels huge, but it's just like building one of your amazing LEGO creations. You need a strong foundation (the introduction), sturdy walls (the main points with facts), and some cool towers on top (the conclusion). Each paragraph is like adding another LEGO brick—one at a time."

This analogy makes a vague task concrete and familiar. It connects the unknown (writing a report) to the known (building with LEGOs), which reduces anxiety and gives them a mental model to follow. It’s a skill that fosters creativity and helps children see solutions where others might only see obstacles. For a deeper dive into fundamental methods and practices, you might find value in a comprehensive guide to improving problem-solving skills.

These strategies—decomposition, pattern recognition, and analogical thinking—are far more than just academic exercises. They are mental tools that empower your child to face the world with curiosity and resilience, knowing that no problem is too big to be broken down, understood, and ultimately, solved.

Using Technology to Build Problem-Solving Skills

In a world filled with screens, it’s easy to feel like technology is the enemy of deep thinking. We often worry about our children passively scrolling or zoning out to mindless videos. But what if we could reframe that screen time? Instead of viewing tech as just a distraction, we can see it for what it truly is—an incredibly powerful tool for nurturing problem-solving skills, when used with heart.

The goal is to help your child shift from being a passive consumer of content to an active creator and thinker. It's about teaching them to use digital tools with intention, turning what could be a time-waster into a dynamic learning experience that they can feel proud of. This isn't about replacing traditional learning but augmenting it, preparing them for a future where digital literacy is absolutely essential.

From Screen Time to Skill Time

The secret lies in guiding your child towards activities that challenge their mind and demand active participation. Many brilliant apps and games are now designed specifically to build logical thinking, strategic planning, and creative problem-solving. A simple switch in the type of digital content they engage with can make a world of difference to their confidence.

Think about the contrast between watching someone else play a game and actually playing it. One requires almost nothing from your child, while the other involves planning, sequencing, feeling the thrill of a challenge, and storytelling—all vital components of complex problem-solving. It’s this active engagement that forges new neural pathways and strengthens their cognitive muscles.

This table shows just how easy it can be to transform common passive habits into powerful learning opportunities.

From Screen Time to Skill Time

| Passive Activity | Active Problem-Solving Alternative | Skill Developed |

|---|---|---|

| Watching gameplay videos | Playing a collaborative strategy game like Minecraft | Teamwork, resource management, and strategic planning |

| Scrolling through social media | Creating a digital scrapbook or a short film about a family holiday | Storytelling, project management, and digital literacy |

| Mindlessly watching cartoons | Using a coding app for kids like ScratchJr to create their own cartoon | Logical sequencing, creativity, and systematic thinking |

It's all about making small, intentional shifts that move the needle from consumption to creation.

Guiding Digital Exploration

You don’t need to be a tech wizard to make this happen. Your role is to be a thoughtful guide. Show genuine interest in their digital world. Ask them to teach you how to play their favourite strategy game. If they’re researching a topic for school, sit with them and explore different online resources together, talking about how to spot a reliable source.

This collaborative approach helps them see technology as a tool for discovery, not just entertainment. It also opens up natural conversations about digital citizenship and critically evaluating information—crucial problem-solving skills in their own right. Exploring different tools and platforms can be a core part of their education, a topic we dive into in our guide to learning in virtual environments.

The future workplace will undoubtedly demand close collaboration with technology. In the UK engineering sector, for instance, a staggering 50% of employers believe that AI integration will significantly improve problem-solving capabilities in their teams. By introducing your child to technology as a thinking partner now, you are laying the groundwork for their future success.

The most important step is to shift the narrative from "less screen time" to "better screen time." When we help our children use technology to create, collaborate, and solve problems, we are not just managing a habit—we are mentoring a future innovator.

Fostering Creation Over Consumption

Encourage projects that require your child to use technology as a creative tool. This could be anything from designing a simple website about their favourite hobby to learning basic coding to make their own game. These activities are incredibly powerful because they give your child a real sense of pride and involve a continuous cycle of planning, testing, and refining.

A child building a game in Scratch, for example, must first break their idea down into small steps (decomposition), figure out the logical sequence of commands, and then troubleshoot when things inevitably don’t work as planned. They are learning to persist through frustration, test hypotheses, and think systematically—all without it ever feeling like a formal lesson.

By embracing technology in a balanced and intentional way, you equip your child with the skills to not only navigate their world but to actively shape it. You teach them that the most powerful tools aren't just for entertainment, but for bringing their own ideas to life.

Adapting Your Approach for Every Unique Learner

The journey to becoming a confident problem-solver is deeply personal. No two children learn the same way or at the same pace, and this beautiful diversity is something we should celebrate, not try to overcome. At the heart of great support lies a simple truth: our methods have to bend to fit the child, not the other way around.

This becomes absolutely critical when supporting children with Special Educational Needs (SEN) or those facing Social, Emotional, and Mental Health (SEMH) challenges. For these learners, the world can often feel unpredictable and overwhelming. Our role is to build a sense of safety and structure, turning moments of potential anxiety into opportunities for quiet triumph.

This is where the principles of differentiated learning come into their own. It’s all about providing support that acknowledges each child’s unique starting point and adjusting the environment, the task, and our expectations to help them succeed on their own terms.

Creating Predictability and Safety

For many children, especially those with SEN or SEMH needs, predictability is the bedrock of confidence. When they know what’s coming next, they have far more emotional and cognitive energy to spare for a new challenge. Creating clear, consistent routines can transform their ability to engage with problems.

This doesn't mean life has to be rigid. It just means providing anchors in their day that help them feel secure.

- Visual Schedules: A simple picture-based schedule for a task like getting ready for school can work wonders. For a child who feels anxious about the morning rush, seeing each step laid out visually—clothes on, teeth brushed, shoes tied—reduces cognitive load and empowers them to manage the task themselves.

- 'First-Then' Boards: This is a fantastic tool for motivation. A board showing "First, we’ll try the tricky puzzle for three minutes, then we’ll have five minutes of tablet time" makes the effort feel manageable. The reward is clear, immediate, and certain, which can be incredibly calming for an anxious mind.

These tools aren't just about managing behaviour; they're about communicating respect for a child's needs. They send a powerful message: "I see you, I understand what helps you, and I am here to support you."

Building Skills Through Story and Structure

Navigating friendships, understanding others' feelings, or managing frustration are some of the most complex problems a child will ever face. These social and emotional challenges require a specific set of skills, and this is where targeted, empathetic strategies can make a world of difference.

Social Stories are a wonderful example. These are short, simple narratives written from the child’s perspective that describe a social situation and offer clear, positive ways to respond.

Imagine a child who gets very upset about sharing toys at nursery. A social story might read: "Sometimes my friend wants to play with my toy car. It's okay to feel a bit sad or worried. I can say, 'You can have a turn in two minutes.' When I share, my friend feels happy, and we have fun playing together. Sharing makes me feel proud."

This simple script gives them the language and the emotional framework to solve a recurring social problem. It doesn’t just tell them what to do; it helps them understand the why, building empathy and social competence along the way.

Celebrating Progress, Not Perfection

This is perhaps the most important adaptation of all. When a child is struggling, their self-esteem is often fragile. They may already feel like they are "not good enough" at certain things, and our response in these moments is everything.

We have to become experts in noticing and praising the small victories.

- Praise the Effort: Instead of just, "You solved it!", try saying, "I am so proud of how you kept trying even when you felt frustrated. That was so brave."

- Be Specific: A generic "Good job!" is easily forgotten. Try, "I loved how you took a deep breath when the blocks fell over. That was a brilliant way to help yourself feel calm."

- Acknowledge the Feeling: Show them you get it. "That puzzle was really hard, wasn't it? I could see how much you wanted to give up, but you didn't. It's amazing that you stuck with it."

By focusing on the process—the effort, the strategy, the resilience—we send a clear message: your worth is not tied to the outcome. This builds a foundation of emotional safety that gives them the courage to tackle the next challenge, knowing that you are cheering for their effort, every single step of the way.

Common Questions About Nurturing Problem Solvers

As you start this journey of intentionally building your child’s problem-solving skills, it’s only natural for questions to pop up. You’ll probably wonder if you're doing enough, if you’re saying the right things, or how on earth to handle those moments when everyone is tired, cranky, and on the verge of giving up.

Trust me, that's completely normal.

Raising a resilient, independent thinker is a marathon, not a sprint. It’s built in the small, everyday moments, not grand, sweeping gestures. This section is here to give you some quick, practical answers to the most common questions we hear, helping you feel confident and stay the course.

What If My Child Gives Up Too Easily?

It’s heartbreaking to watch your child dissolve into tears or declare "I can't do it!" the second a challenge appears. This isn't a sign of failure—on their part or yours. It’s simply a signal that their frustration has boiled over and they’re emotionally flooded.

The key here is to step in not as a rescuer, but as an emotional co-regulator.

First, always validate their feelings. Something as simple as, "This is really tricky, isn't it? I can see you're feeling so frustrated," can work wonders. It tells them their feelings are valid and that you’re on their team.

Once they feel heard and a little calmer, gently shift the focus back to the process. Break the problem down into the tiniest possible first step. If they’re overwhelmed by a puzzle, you might say, "This is too much right now. Let's just find one piece with a straight edge. Just one. Can we do that together?" Celebrating that tiny win can provide just enough momentum to try the next small step.

Am I Helping Too Much or Not Enough?

Ah, the million-dollar question! Finding this balance is one of the trickiest parts of the whole process. There’s no single right answer because it depends entirely on your child's emotional state and the specific task.

A good rule of thumb is to use the "scaffolding" approach—provide just enough support to keep them from collapsing, then step back as soon as they’ve found their footing again.

Think of it like teaching them to ride a bike. At first, you hold the seat firmly. Then, you just steady it with a few fingers. Finally, you let go, but you stay close enough to catch them if they wobble, ready with a comforting hug if they fall.

Here’s a practical way to check in with yourself:

- Are my words guiding or giving? "What could you try next?" is a guide. "You should do it this way," gives the answer away.

- Am I solving the problem or managing the emotion? Your main job is to help them handle the frustration so they can solve the problem.

- Have I offered a tool instead of a solution? Suggesting they take a deep breath, try a different angle, or take a five-minute break are all tools they can use for a lifetime.

How Can I Apply This to Older Children and Teenagers?

The core principles don't change as children get older, but the context and your role certainly do. With teenagers, your partnership shifts from direct guidance to more of a sounding board. They need the space to grapple with more complex, real-world problems on their own terms, even if it feels scary for us.

This is where you can encourage them to apply their skills to bigger challenges, like managing their revision timetable, navigating a tricky social conflict, or even analysing real-world data. For instance, initiatives like the ONS Data Challenge in England and Wales engage students aged 16 and over in using real data to solve problems, showing them exactly how these skills apply to future careers. To see what that looks like, you can explore the ONS Data Challenge in more detail.

With teens, your most powerful tool is the curious question. Instead of jumping in with advice on a friendship issue, try asking, "That sounds so tough. What outcome are you hoping for here?" or "What are a few different ways you could approach that conversation?" This respects their autonomy while gently guiding their thought process.

What If We Don't Have Time for This Every Day?

Let’s be realistic. Life is hectic, and some days are purely about survival. Please, don’t feel pressured to turn every single challenge into a deep learning moment. The goal is consistency, not perfection.

If you're running late and your child is struggling with their coat zip, it's absolutely fine to just do it for them. No guilt allowed.

The key is to be intentional when you do have the time and emotional bandwidth. Aim for a few high-quality moments a week where you can consciously step back and let them struggle productively. It's the cumulative effect of these moments over the years that builds a truly resilient problem solver.

Ultimately, your presence, your patience, and your belief in your child's ability to figure things out are what matter most. Every time you pause before jumping in, you're sending a powerful message: "I trust you." That trust is the very foundation their confidence is built on.

At Queens Online School, we believe in nurturing these essential life skills within a supportive and structured learning environment. Our approach is built on empowering students to become confident, independent thinkers, ready to tackle any challenge. Discover how our personalised online curriculum can help your child thrive.